Monday, November 12, 2007

Send Me Your Faves

Now scroll down and read!

And while you're at it, go to my website www.noahbudin.com and sign up for my newsletter. You can read past newsletters in the archives at http://www.noahbudin.com/newsletter.php.

Thanks!

Sunday, November 11, 2007

On Songwriting: Opening Lines

“I’m the kid who ran away with the circus…”1

“There’s a young man dying as he stands beside the sea…”2

“I saw a stranger with your hair, tried to make her give it back…”3

“You want to dance with the angels? Then embroider me with gold…”4

“Couple in the next room bound to win a prize. They’ve been going at it all night long…”5

“If I leave here tomorrow, would you still remember me…?”6

“I put on my blue sued shoes and I boarded a plane…”7

“Moving in silent desperation, keeping an eye on the

“Wasted and wounded, it ain’t what the moon did, I’ve got what I paid for now…”9

“If I had a boat, I’d go out on the ocean. And if I had a pony, I’d ride him on my boat…”10

“War. What is it good for? Absolutely nothing.”11

“I was born in a crossfire hurricane…”12

“I met her on a Monday and my heart stood still…”13

“When I find myself in times of trouble, Mother Mary comes to me…”14

How important are the first lines of songs? If you’ve read any of my words before this point, you’d know that I’d say EVERY word is important (see “Wasted Words”). But your opening lines carry a special weight. They are not necessarily more important than any other line, but they serve a special purpose.

In fact, each segment of a song’s structure has a designated purpose. We’ve talked about structure before – verse, chorus, verse, chorus, bridge, etc. Now, let’s break that structure down into micro-units and macro-units.

When I queried my musical friends about opening lines, one of them reminded me that many of the classics from the 1930’s and ‘40’s had an entire introductory verse, unlike the rest of the song musically, and largely forgotten soon after the “meat” of the song stayed in our collective memories. Most of us know, or have heard, the song “Over the Rainbow” by Harold Arlen and E. Y. “Yip” Harburg. We know it opens with the lyric “Somewhere over the rainbow…” But, it doesn’t. There’s an entire opening verse:

When all the world is a hopeless jumble

And the raindrops tumble all around

Heaven opens a magic lane

When all the clouds darken up the skyway

There's a rainbow highway to be found

Leading from your window pane

To a place behind the sun

Just a step beyond the rain

Somewhere over the rainbow…

This was the accepted style then. I suspect it also had to do with getting the listener’s attention. Or, rather, giving the listener a little prep time to focus on the “meat” of the song to come, to guide them in gently – a little meditation time, or foreplay. (I suppose a comparison can be made to the “curtain raiser” in a Broadway musical. This is the song that opens the second act. It’s usually one of the weaker songs in the show, or a throw-away number, by design. At the start of act II, the audience is still in the lobby, eating snacks, in the bathroom, engrossed in conversation, finding seats, etc. The opening number is there to bring the audience in and focus them on the rest of the play to come. Do you remember the opening song for act II of “Fiddler on the Roof?” Probably not. You probably remember much of the great music – “

When songs do have an intro, it’s usually a short musical intro – the last four bars of the main musical statement is common. So, you need to draw your listener in in a hurry. You need to set the mood, establish the tenor, and set up the story in two to four lines. That’s not to say the mood and tone can’t change. Listen to a Meatloaf’s “Bat Out of Hell,” or Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody.” But you’ve got to lead your listener into the song and give him some expectation, maybe create a little anticipation, about where you’re going to take him. There can always be surprises. And surprises can be good.

Look at the above examples. Some of them are from well known songs and you may recognize them, and some you may have never heard before. I’ll opine about a few of them here, but look at them and think about where they take you and how (or if) they serve their purpose. I’m sure you can come up with your own list, and that might not be a bad exercise.

When Edwin Starr sang, “War. (Huh! Yeah!) What is it good for? Absolutely nothing!” there was no doubt about the intentions of this song and where it was going to go. On the flip side (metaphorically), John Gorka surprises us in the first fourteen words of the song I quoted above. He starts out with a fairly benign and common observational comment: I saw a stranger with your hair. It could be a conversation starter, small talk. But, he says what we least expect: tried to make her give it back. It is all at once surprising and funny and a little unsettling, maybe a little disquieting. It usually gets a laugh when he does it live. We know we’ve been set up – but for what? We’ve been drawn into this lyric, and as we listen to the story unfold, we realize that he’s taking us somewhere very deep, even bordering on pathos (Gorka’s good at pathos). There are surprises in each verse, but he set us up to expect surprises. And he never strays from his topic (the person to whom he’s singing) which he also set up in that first line. It’s a beautifully crafted song.

Paul Simon – pick any of his songs, he’s a study in lyrics in and of himself – gets us going with, “Couple in the next room bound to win a prize. They’ve been going at it all night long…” Makes you want to know more. And with Paul, you know you’re in for a well-spun tale; start the fire, get comfortable. On the other hand, when Mick Jagger wings into, “I was born in a crossfire hurricane…” you know you’re in for a wild ride.

Obviously, there are many other factors that contribute to what we expect from a song within the first few bars – tempo, chord progression, instrumentation, the sound of Paul Simon’s voice versus Mick Jagger’s voice, etc. But, like building a house, the lyric is the frame of the song on which everything else is hung, whether it’s a thirty-six room mansion or a yurt. Or even: I met him on a Monday and my heart stood still. The do run run run, the do run run.

1“The Kid” by Buddy Mondlock

2“Young Man Dies” by David Wilcox

3“I Saw a Stranger With Your Hair” by John Gorka

4“Dance With the Angels” by Lisa Loeb

5“

6“Free Bird” by A. Collins/R. Van Zant

7“Walking in

8“Walking Man” by James Taylor

9“Tom Traubert’s Blues” by Tom Waits

10 “If I Had a Boat” by Lyle Lovett

11 “War” by N. Whitfield/B. Strong

12 “Jumping Jack Flash” by M. Jagger/K. Richards

13“Do Run Run” by J. Barry/E. Greenwich/P. Spector

14“Let It Be” by Lennon/McCartney

Saturday, November 03, 2007

On Songwriting: Music and Lyrics, or Lyrics and Music? REVISED

Everyone has a different way of working. And everyone probably has several different ways of working. In fact, if you, as a creative person, do lock yourself into a set, predictable formula for receiving ideas and expanding on them, your work will most likely become stale. Creative people need to be open to new stimuli, and be flexible with work habits. Creative people should look for and embrace opportunities to go out of their comfort zones.

So, there is no one, good, straight answer to the question “what comes first, melody or words?” I’ve written both ways. As I’ve said, the words, or some lyrical or thematic idea, are usually my impetus in writing a song. But, I do not like to write lyrics in a vacuum, that is, in a lyrical vacuum. Many of my best songs evolve when lyrics and music are developed together. I may get the lyrical idea first, but then I need to pick up the guitar and see what those lyrics suggest musically. In turn, I let the music suggest lyrical ideas, as well.

One thing I do believe: Music and Lyrics should live together in harmony. I’m not talking about the actual harmonic structure. I’m using the word “harmony” as in “the citizens of the world should live together in harmony.” Or, Lyrics and Music should have synchronicity. That is, they should go together, and they should sound like they go together. Pretty simple, eh?

But, you might be surprised at how many times I hear a song whose melody does not match the lyrics, or whose style does not match the subject. Just as your lyrics should express precisely the message you want to get across, your melody should support those words. Your music is just as emotively expressive as your words. It’s a complete package.

I did an experiment once. I didn’t know it was an experiment at the time, but I’ve come to see it as one. It concerns the music of the songwriter I mentioned in the previous chapter. I was explaining my dislike for this songwriter’s songs and one of the things I was demonstrating was his lack of attention to the relationship between melody and lyrics. My audience of one was skeptical, so I took my guitar and sang the lyrics to one of his hits to the melody of another one of his hits. The point wasn’t that I could manipulate the tempos and rhythms to fit. But, the point was made when someone in the next room poked her head in the door and, with obvious sincerity delight, said, “Oh, I love that song!”

That really shouldn’t happen. I would want even a casual listener to my music to say, “That doesn’t sound quite right.” Every song should be distinct in its personality. I find it much easier in print to describe lyric writing that melody writing. And who am I to say what makes a melody “good?” For me, it’s more intuitive. I have taken music theory classes and piano lessons. My last ones were many years ago and my skills are rudimentary. But I do understand the relationships between notes and intervals, major and minor. I have the vocabulary to communicate ideas. I understand concepts like relative minor, key signature, I, IV, V, meter signature, tempo, diminished, triads, sevenths, suspensions, timbre, legato, etc. I have the foundation.

I also know, as noted in an earlier chapter, that words have a natural rhythm. And words have a natural modulation of pitch and tone. So, just as you can train yourself to hear the natural rhythms in words and phrases, you can train yourself to hear the natural modulations in pitch and tone. Speak your lyrics out loud, conversationally. Disregard the rhyme scheme and patterns for the moment. Where does your voice want to go? Listen to the natural “ups and downs.” I once heard a songwriter suggest that one should walk with one’s lyrics. That you should literally take a walk and recite or think of your lyrics. There are natural rhythms and patterns to walking and your gait will change with your mood or ideas. And “walking your lyrics” connects them to something physical. You get that whole body sensation, you experience the lyrics kinesthetically. And all of this may help to suggest where your lyrics want to go melodically.

There are other factors that suggest where your melody might want to go and what kind of style or tone your music should have. Is your song an “angry” song? A love song? An angry love song? If it’s a song about flying, either literally or metaphorically, perhaps your melody should “soar.” Maybe your melody wants to have an upward motion to support the ideas. Your job is to capture a mood, a feeling, an ambiance. Tempo, time signature, lush chords, sparse lines, chord progressions, major sevenths, open fifths, even key signature – these all make a difference.

I can tell you that (but I can’t tell you how) your melody must be strong. I know that’s a very fuzzy statement. But, when I was young and trying to write songs, my brother David, eleven years my senior and already a professional in the music industry, said something like that to me, with no other explanation, and it stuck with me from that day to this. “Your melody has to be good.” It should, in most cases, be able to stand on its own. It should be strong enough that if you stripped away all of the instruments, harmonies and production, it would be able to carry you bareback where it wants you to go.

I didn’t need any other explanation – I let the music do the explaining. David’s simple instructional phrase was all it took to open my ears up to the sounds of melodies. And, once again, I guess I must refer back to the concept that part of this process is innate. I know what I like, you know what you like. Practice listening to melodies with new ears and try to identify why you like it. If you have the theory background and can intellectualize it, go right ahead. But whether you can or can’t, emulate. Yeah, copy. Emulation is one of the best ways to learn any art. You’ll eventually develop your own voice. A good, strong melody...? To paraphrase Chief Justice Potter Stewart, I can’t define it, but I know it when I hear it.

In general, I think a melody should be somewhat predictable, but it should have some surprises as well. By predictable, I don’t necessarily mean an imitation of someone else’s melody, although it may be evocative. It may be evocative of a lot of things. But, it’s the predictability, or familiarity, that can invite and draw a listener in, give him some comfort, and make him want to stay for the ride (and the twists and urns the ride may have to offer). By surprises, I don’t mean you should jar the listener, but take them to a new place. Use an unexpected chord in the progression, jump an octave in the melody (if it’s supported lyrically) or employ an unanticipated interval.

In my song “Edge of the Ocean,” I use a fairly simple chord progression – I, VI, IV, I, V – but I take the melody in unexpected directions. It starts on the keynote in an upper octave and then jumps down a fifth – or from a B to an E. This happens while the chord is shifting from the major I to its relative minor VI. The first six notes are very simple: three notes up the scale and three notes back down. And then the jump to the fifth below. Or: C, D, E, D, C, B, (down to) E. In context, it’s not jarring. And that interval jump helps to highlight, or spotlight, some of the important words` and ideas in the song. It draws attention to that spot and, instead of throwing the listener off, it pulls them closer.

There are so many good melody writers, past and present. Listen to them. Listen to Gershwin, Berlin and Porter. Listen to Don MacLean’s “Empty Chairs” and “Vincent.” Listen to Teddy Geiger, he writes a great pop melody, as does Lisa Loeb. Listen to the simple eloquence of that song “Delilah” by The Plain White T’s. On the far end of the spectrum is Joni Mitchell. Listen to her album “Blue.” Her melodies take twists and turns and leaps that would scare a circus acrobat, but she makes it work. And on the other end of the spectrum you might find Leonard Cohen.

Lyrics and music together should sound natural, as if they had always been that way. It should be seamless. The listener should not be able to hear the songwriting process. That’s distracting. When you’re watching a film or a play, and you notice The Acting or The Directing or The Lighting or The Photography, when any one of the individual elements stands out to you, it’s a distraction. You may still enjoy the event, and that’s OK. But, it’s those rare pieces of art and entertainment that transcend all of that. They pull you in and you forget that you’re watching a Performance. It’s when you don’t notice the hard work and skill and time and effort that went into it, when it looks easy, that something close to artistic perfection, if I may even suggest that such a thing exists, is achieved.

Monday, October 22, 2007

On Songwriting: Music and Lyrics, or Lyrics and Music?

The answer to this chapter’s titular question is “yes.” There is no one way, better way, right way or wrong way to write a song. I’ve written a lot about lyric writing, to this point, because that’s usually where songwriting starts for me. And, often, as a listener, I tend to get drawn in by the lyrics. I say “usually” and “often” because there is no locked and set formula for me.

Everyone has a different way of working. And everyone probably has several different ways of working. In fact, if you, as a creative person, do lock yourself into a set, predictable formula for receiving ideas and expanding on them, your work will most likely become stale. Creative people need to be open to new stimuli, and be flexible with work habits. Creative people should look for and embrace opportunities to go out of their comfort zones.

So, there is no one, good, straight answer to the question “what comes first, melody or words?” I’ve written both ways. As I’ve said, the words, or some lyrical or thematic idea, are usually my impetus in writing a song. But, I do not like to write lyrics in a vacuum, that is, in a lyrical vacuum. Many of my best songs evolve when lyrics and music are developed together. I may get the lyrical idea first, but then I need to pick up the guitar and see what those lyrics suggest musically. In turn, I let the music suggest lyrical ideas, as well.

One thing I do believe: Music and Lyrics should live together in harmony. I’m not talking about the actual harmonic structure. I’m using the word “harmony” as in “the citizens of the world should live together in harmony.” Or, Lyrics and Music should have synchronicity. That is, they should go together, and they should sound like they go together. Pretty simple, eh?

But, you might be surprised at how many times I hear a song whose melody does not match the lyrics, or whose style does not match the subject. Just as your lyrics should express precisely the message you want to get across, your melody should support those words. Your music is just as emotively expressive as your words. It’s a complete package.

I did an experiment once. I didn’t know it was an experiment at the time, but I’ve come to see it as one. It concerns the music of the songwriter I mentioned in the previous chapter. I was explaining my dislike for this songwriter’s songs and one of the things I was demonstrating was his lack of attention to the relationship between melody and lyrics. My audience of one was skeptical, so I took my guitar and sang the lyrics to one of his hits to the melody of another one of his hits. The point wasn’t that I could manipulate the tempos and rhythms to fit. But, the point was made when someone in the next room poked her head in the door and, with obvious sincerity delight, said, “Oh, I love that song!”

That really shouldn’t happen. I would want even a casual listener to my music to say, “That doesn’t sound quite right.” Every song should be distinct in its personality.

I find it much easier in print to describe lyric writing that melody writing. And who am I to say what makes a melody “good?” For me, it’s more intuitive. I have taken music theory classes and piano lessons. My last ones were many years ago and my skills are rudimentary. But I do understand the relationships between notes and intervals, major and minor. I have the vocabulary to communicate ideas. I understand concepts like relative minor, key signature, I, IV, V, meter signature, tempo, diminished, triads, sevenths, suspensions, timbre, legato, etc. I have the foundation.

I also know, as noted in an earlier chapter, that words have a natural rhythm. And words have a natural modulation of pitch and tone. So, just as you can train yourself to hear the natural rhythms in words and phrases, you can train yourself to hear the natural modulations in pitch and tone. Speak your lyrics out loud, conversationally. Disregard the rhyme scheme and patterns for the moment. Where does your voice want to go? Listen to the natural “ups and downs.” I once heard a songwriter suggest that one should walk with one’s lyrics. That you should literally take a walk and recite or think of your lyrics. There are natural rhythms and patterns to walking and your gait will change with your mood or ideas. And “walking your lyrics” connects them to something physical. You get that whole body sensation, you experience the lyrics kinesthetically. And all of this may help to suggest where your lyrics want to go melodically.

There are other factors that suggest where your melody might want to go and what kind of style or tone your music should have. Is your song an “angry” song? A love song? An angry love song? If it’s a song about flying, either literally or metaphorically, perhaps your melody should “soar.” Maybe your melody wants to have an upward motion to support the ideas. Your job is to capture a mood, a feeling, an ambiance. Tempo, time signature, lush chords, sparse lines, chord progressions, major sevenths, open fifths, even key signature – these all make a difference.

I can tell you that (but I can’t tell you how) your melody must be strong. I know that’s a very fuzzy statement. But, when I was young and trying to write songs, my brother David, eleven years my senior and already a professional in the music industry, said something like that to me, with no other explanation, and it stuck with me from that day to this. “Your melody has to be good.” It should, in most cases, be able to stand on its own. It should be strong enough that if you stripped away all of the instruments, harmonies and production, it would be able to carry you bareback where it wants you to go.

I didn’t need any other explanation – I let the music do the explaining. David’s simple instructional phrase was all it took to open my ears up to the sounds of melodies. And, once again, I guess I must refer back to the concept that part of this process is innate. I know what I like, you know what you like. Practice listening to melodies with new ears and try to identify why you like it. If you have the theory background and can intellectualize it, go right ahead. But whether you can or can’t, emulate. Yeah, copy. Emulation is one of the best ways to learn any art. You’ll eventually develop your own voice. A good, strong melody...? To paraphrase Chief Justice Potter Stewart, I can’t define it, but I know it when I hear it.

Your lyrics and music together should sound natural, as if they had always been that way. It should be seamless. The listener should not be able to hear the songwriting process. That’s distracting. When you’re watching a film or a play, and you notice The Acting or The Directing or The Lighting or The Photography, when any one of the individual elements stands out to you, it’s a distraction. You may still enjoy the event, and that’s OK. But, it’s those rare pieces of art and entertainment that transcend all of that. They pull you in and you forget that you’re watching a Performance. It’s when you don’t notice the hard work and skill and time and effort that went into it, when it looks easy, that something close to artistic perfection, if I may even suggest that such a thing exists, is achieved.

Thursday, August 16, 2007

On Songwriting: Inspiration - Part Three

Writers of any genre often talk about the discipline it takes to be a successful writer. And I believe it. As I’ve said before, once you realize you’ve got the God-given (or natural) talent, it’s up to you to hone and nurture it. Once you’ve learned the rules, you can’t just stop there. And you’re never really done learning the rules anyway.

Think about a professional athlete. It’s one thing to be able to throw the ball at 90 mph, but it’s quite another to pinpoint the spot where you want it to go and then get it there. Some people have spent a lifetime studying and understanding the rules and plays and nuances of a sport, but you wouldn’t want to see them on the field. The professional athlete realizes that he or she was born with some sort of ability and then works very hard to master that ability. It takes practice.

I’ve read and heard writers in interviews describe their daily rituals. Some get up at

The discipline, the just doing it, I think, is important. Indeed, professional songwriters, that is people who actually make their living writing songs (think of the old

When I was in college, I met a famous singer/songwriter. I didn’t much care for this singer/songwriter’s work, but he was wildly popular and had sold many records. A friend dragged me to the concert, countering my protests with the old “you’ve got to see him live and in person” promise. I still didn’t like him. Actually, I had nothing against him. It was his songs I couldn’t stand. But, he was a famous, working singer/songwriter, and I was an aspiring, not-famous singer/songwriter, all of 19 years old. So, when I found that this famous persona was completely accessible after his concert, I stood in line with everybody else, shook his hand with everybody else, and waited until everybody else had left the building, and then I stalked him. My friend and I slipped backstage and followed him into his dressing room, and when he turned around and saw us I stammered, “I’m a songwriter, too!” I’m not sure what I was hoping to get out of this – maybe a “well, here’s my guitar, let’s hear what you got. That’s fantastic! I’ll put you in touch with my label!” That didn’t happen. What I got from this famous, working songwriter with many albums under his belt and a world-wide following was, “Well, I hope you’re not one of those songwriters who need to be inspired.”

Of course I was! I was flabbergasted. I don’t remember if I said anything after that or not. All I remember was being confused and speechless. And knowing that my record contract was not materializing that day. And, I used this encounter for many years to “prove my point” about how bad this guy’s songs were. But I was wrong to do that. I still don’t like his songs, but, whether I admitted it or not (and I didn’t for many, many years), I learned a valuable lesson that day. Working songwriters work.

As songwriters, we need to find ways to be inspired and sit down with a workman-like approach. Some writers carry note cards with them where ever they go so they can jot down ideas when the muse visits. Sometimes they just write down observations about the world around them. That’s a way of being, and being prepared to be, open to receive. I would be better served if I wrote down more things. I tend to rely on my memory which, I always forget, is practically nonexistent. I know a songwriter who wakes up in the middle of the night with ideas and sings them into his answering machine, the nearest and most accessible device at his disposal, for later retrieval. His family has gotten used to hearing weird little snippets of unwritten songs being sung by a very tired man when they listen to messages. They’ve also learned not to erase them. Every writer needs inspiration. But, every writer needs to practice their craft. Forever.

(I think it might have been Pablo Casals who said he never says he learned how to play the cello because “learned” implies that he’s done learning everything he possibly can about the instrument. He says one must never stop learning one’s craft.)

So, where do you get ideas? Teach yourself to be sensitive to sounds and rhythms. Let words create images in your mind. Expose yourself to all kinds of stimuli. Learn how to open yourself up to the divine and spiritual powers in the universe. Be open to receive. And think of them in your head.

Monday, August 13, 2007

On Songwriting: Inspiration - Part Two

There’s a quirky little book out there by W. A. Matheiu, published in 1991 called “The Listening Book.” I discovered this book by accident one day while rummaging around a used book store. I was teaching music to preschoolers and middle-schoolers at the time and I immediately started adapting much of what the author was talking about and incorporating it into my lesson plans, my teaching strategy, my pedagogical philosophy and my own approach to life in general, and life as a musician and songwriter specifically.

Matheiu is a composer and musician and, among other things, worked (as a pianist) with improvisation groups such as

In his book, he talks about different kinds of listening. As a songwriter, I know I hear things differently than most people. Listening is, or should be, an active, not passive, undertaking. (We can try to play with the semantics and make distinctions between “hearing” and “listening.” But, let’s not.) As I’ve alluded to earlier, listening, for me, is a whole body experience. I hear words and sounds and breathe them into my body. I let them occupy space beyond my ears.

Sometimes, especially when I’m “open to receive,” ordinary words and phrases pop into my head and all of a sudden take on a new, or previously unperceived, meaning. It can be a word or a phrase I use a hundred times a day and suddenly I’ll hear a rhythm, or a sound, or, more importantly, an idea or see an image, that take that word or phrase in a whole new direction. I hear in colors. I hear in shapes. I hear in images.

I’m aware that there’s a condition, or psychological phenomenon, called synesthesia, where one’s senses are more intertwined than usual. People with synesthesia report seeing colors when music is played, for example. It varies in different people. Some see a color, even in different shapes, for certain sounds, like the telephone ringing, or see a specific color for each letter of the alphabet or number, or word. It’s more common in children, but some never “outgrow” the condition. I don’t know that what I experience is synesthesia, but, whatever it is, I like it.

I think people, especially people who are in the arts, can learn to be more perceptive and sensitive to the world around them. I think we can consciously make ourselves more open to receive and, thus, become inspired. It takes practice and deliberate effort, but, like anything repeated, becomes habit and natural and commonplace. So, learn to be open to new ways to experience words and sounds and the world around you, whatever that means for you.

Different people are inspired in different ways by different things. I’m a title person. I like the way titles sound – song titles, poem titles, book titles. If I get an idea for a title, that’s often enough inspiration for me to, at least, get me started. I’ve learned over the years not to force the process. When I get a really good idea for a title in my head, I know better than to sit down and try to make myself write a song. I’ve done it, and those songs usually don’t make the cut. They sound, well, forced. I do sit down and see if anything worthwhile happens. I might get some usable ideas or material, and if it all flows out all at once, all the better. But that usually doesn’t happen. I know my own process. I know that if I let the idea steep, if I let that title rattle around in my head for a while, that the song will reveal itself to me when it’s ready for me to do some serious work with it.

(There is something to be said for discipline. And I’ll say it later.)

But, it doesn’t always happen that way as described above. Sometimes I’ll write a song and find no discernable title within its lyrics. That’s happened to me specifically with my songs “Joshua’s Band” and “Edge of the Ocean.” “Joshua’s Band” was named by a 7th grade student of mine at the time when I played it for a class and told them I couldn’t think of a title for it. “Edge of the Ocean” probably still isn’t the best title for that song, but it’s the one that emerged over time and stuck.

Many more of my songs, however, have started with the germ of a title. “With These Hands” is one notable example. In fact, when I thought of it, I thought it was such a good title – a title that got right to the crux of what I wanted to say, that had such a strong, fully developed image – that it must have been written already. I thought I must have heard it somewhere before and stored it in my subconscious where it was waiting to be plagiarized. I went around asking people, before I had one word or note written, if they had heard of the song “With These Hands.” It was such a good title that some said they had. This was, if you can imagine such a time, before the days of Google. I did some research, and when I was satisfied that the title, and more importantly, the idea, was not already a song, or at least not a well known song, I set to work on it. Titles aren’t copyrighted anyway.

So, how did the idea come to me? I don’t know. I was thinking about hands. I may have been thinking about that line in one of my favorite Paul Simon songs called “

Oh, oh, what a night

Oh, what a garden of delight

Even now that sweet memory lingers

I was playin’ my guitar

Lying underneath the stars

Just thankin’ the Lord

For my fingers,

For my fingers

I was thinking about all of the things hands can do: build great structures, plant tiny seeds, cause destruction, tenderly wipe tears, be used as weapons, or instruments of passion. I probably said something to myself like, “I wrote that whole song with these hands.” Then, because I’ve attuned myself to hear these kinds of things, because I was open to receive, the phrase “with these hands” jumped out at me and said “hey, there’s a song in here!” I’m an impatient songwriter. But, because I’ve learned when to push it and when to leave it alone, this song took over a year to complete. I waited for the direction of the second half of the song to reveal itself to me, and, when it finally did, it was worth it.

“Metaphor” is another title that jolted through me like a lightening bolt. You could almost see the light bulb above my head. How many times have I read, said or used the word “metaphor” in some other context and not realized that there was a song there? But, this time, I was open to receive. I was driving – and I remember exactly where I was – and suddenly that word came into my head and I knew what kind of song I wanted to write. I had no structure, I had no melody, I had no inkling of tempo or style. I just knew that I had an idea worth waiting for and exploring. I knew that the word “metaphor” would probably not even be in the lyrics, but that there would be a list of some kind. The seed had been planted and was ready to be patiently tended and nurtured.

“The Silent Son” and “She Knows God” are some of the other songs that have sprung from their titles. And I wrote a poem once based on the phrase “one single act of kindness.” That phrase had been rattling around my brain for a long time, maybe a year, before it revealed to me what I should do with it. I knew it would be a good title. It has a natural rhythm and it’s suggestive…of something. It could have gone in any number of directions. I’m going to reprint it later as an example of something else in another chapter, but the point is here that it doesn’t really matter where it went, but how it came to be; Words, sounds, shapes, rhythms, and how they evoke some reaction or emotion, and how you need to be sensitive to it. Be open to receive.

Often, for me, titles are more than just the names of the songs. They encompass much of the meaning of the song. They are evocative. They can act as a compass, or an anchor, much the way that a mission statement can (and should) guide a business or organization. A good, clear mission statement will guide everyone in the organization, from part time volunteers to cleaning staff to board members to administrative staff, toward the same goal; it will let each person know exactly how to do his or her job. That’s what a good title does: it guides and informs every word in the song.

Monday, August 06, 2007

On Songwriting: Inspiration - Part One

Ah, inspiration. You can’t teach it. Just as you can’t teach a politician how to have charisma, or a performer to have stage presence, or someone to feel the Holy Spirit move through them. But, you can learn to be open to it. Or, at least you can learn about being open to it.

One of my favorite quotes about creativity and inspiration was in an interview with an author. As is typical, I don’t remember who the author was, but it seems to me that it might have been Kurt Vonnegut, or someone like him – prolific and insane and amazing. Or maybe Edward Albee. He said something like, “People always ask me, ‘where do you get all of your ideas?’ And I say, ‘I think of them in my head.’”

There’s not much more I can add to that. It kind of sums it all up. Anything else I add will just be redundant. So, here I go.

If you look up the word inspire or inspiration in the dictionary, you get a lot of definitions, but not much help. The American Heritage Dictionary offers one definition for inspiration as: Stimulation of the mind or emotions to a high level of feeling or activity. OK. Most other dictionaries also state that inspiration is related to a divine influence on the mind and soul of humans. And they also concur that inspiration has something to do with the respiratory system, as inhaling. I like the idea of combining those definitions and coming up with an image of breathing God, or whomever or whatever is divine to you, into your lungs. Literally, physically breathing God into your body and trusting that power to stimulate you.

I often think of breathing as one of the most intimate and holy acts one can do, in fact, must do. I believe that we breathe, or that it is possible to breathe, more into our bodies than just air (and I’m not talking about pollutants). When I taught music to children in schools, I would have them lie on the floor on their backs, close their eyes, play a recording of Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata,” and tell them not only to listen to it, but to breathe it into their bodies. To let those perfect, haunting, sublime notes enter them and occupy space, to feel the music. I would do this with children as young as first grade, and I would watch them do it and get it.

I’ve used the image a few times in my songwriting. As mentioned in “Wasted Words – Part One,” in my song “She Knows God” I wrote:

But she always breathes the air that surrounds her

And it fills her with more than just breath

And in my song “Haruach” I allude to it this way in the bridge:

To everything there is a season

A time to mourn, a time to pray

And I don’t even know the reason

But it moves through me every day

Many artists have many different analogies about inspiration and ideas. And there are essays and books on the subject. One excellent book is called “The Artists Way: A Spiritual Path to Higher Creativity” by Julie Cameron. She talks about opening yourself up to the creative forces in the universe, like an antenna pulling in reception. I think it’s since I read that book that I’ve used the analogy in a way that sounds more like a sports metaphor. I’m not much of a football fan, but I call it “being open to receive.” Actually, it also comes from certain spiritual cultures, such as the Shakers, who never attribute their hymns as “written by Brother so-and-so,” but as “received by Brother so-and-so.” I once heard Arlo Guthrie in concert liken getting ideas for songs to fishing in a river. You sit there with your pole and line in the water and every once in a while you get a bite and pull something out. The ones you miss keep going downstream for someone else to get. He said he was just glad he didn’t live downstream of Bob Dylan.

* * *

I’m inspired by words. And images. Especially words that create images. I’ve become attuned to hearing words differently than most people. I hear the sound of words. I hear the shape of words. I hear the natural rhythms that words create.

When I do songwriting workshops, where our goal is to write a song as a group in a given amount of time, once the topic is chosen, I start by brainstorming. I have a large piece of paper and a marker and I’ll usually start by saying, “Tell me everything you know about…” I’ll start jotting down the phrases and when my ear picks up some sound or rhythm or image, I’ll probe more along that line. I’ll ask leading questions. I try to make them think in unusual ways. I like unusual word combinations. When someone raises their hand tentatively and then says, “Forget it, it was a dumb idea,” I’ll make them say it anyway because, often, it’ll be the phrase that that ends up driving the song. People are afraid to explore, to get out of their comfort zones. Don’t be.

In this first part of the exercise, I tell them not to rhyme. I try to prompt them to dig deep and get away from those stock phrases and ordinary images. If the topic is “peace,” for instance, we usually need to dig way down because it’s a topic that’s been written about so much and it’s so easy to become cliché. When I say, “Tell me everything you know about peace,” inevitably they’ll start with things like, “not war,” “love,” “calm,” and “quiet.” Those are broad generalizations. We need to get more personal. We need to localize and identify one aspect of peace. If I’m lucky, someone might say “harmony.” Now we’re scratching at the surface of an image. I’ll probe. “What is harmony?” “It’s singing together.” A good image. “It’s putting separate parts together.” “It’s individual voices coming together for a single purpose.” Now we’ve got some stuff on which to build.

I might ask, “Who uses harmony.” “Singers.” “Voices.” “A choir.” Now we personalize. “Pretend you’re in a choir. What would you be doing or thinking?” Someone might say, “We come to this place from our own separate lives. Each one of us alone can’t do this, but together we are strong.” Well, that’s damn near a song. I’ll write that down verbatim, but I’ll keep going to mine some more ideas. I don’t want them to get hung up on rhythm or meter or rhyme yet. When we’re ready, I’ll come back to that and it’ll become our focal point or, at least, our starting point.

First, listen to the natural rhythm of the sentence:

We come to this place

From our own separate lives

Then, of course, there’s the message. And, finally, but in no way less important, is the image. There’s a solid concrete metaphor going on here.

Now we need to shape it.

We come to this place

From our own separate lives

Each one of us alone can’t do this

But together we are strong

And now I introduce rhythm, meter and rhyme. The first two lines have a natural flow already, so we’ll just leave them as they are for now. “Each one of us alone can’t do this” is a little awkward and doesn’t fit the meter. “How can we rephrase this, keeping the intent, but adhering to the rhythm?” (Limitation? No! Opportunity!) How about:

We come to this place

From our own separate lives

We can’t do this alone

But together we are strong

That’s good. But it doesn’t rhyme. Does it have to? No. But I like songs that rhyme. And, unless you’re Paul Simon (“The Boxer”) it’s very difficult to pull off. But, before we begin rhyming, let me point out a couple of things about this quatrain that may influence our rhyme and, probably, the rest of the song, both in structure and message. I like the phrase “this place” in the first line. I like that it is not specific (yet). It can give us an opportunity to reveal what or where “this place” is later in the song. Or, it can just be this place, the one in which we are singing right now. It can be the “everyplace.” In your home, on the streets, in the White House.

A digression: I know I keep saying “be specific” and “create images.” But there’s this dichotomy. An actor always needs to be specific in his choices. But he will also know the rule about “less is more.” And a good actor will know when to use it. It’s the same in songwriting. Sometimes, less is more. Let the listener use her imagination. The specific is already in the message – uniting for peace. Let “this place” be any that the listener chooses. It will be a stronger choice for that listener than you could have made. And you can always get to “that place” later in the song if the song leads you there. Maybe the reveal can be in a bridge that would go something like:

We will gather at the pulpit

We will march on city streets

We will sing it from the mountains

We’ll tell everyone we meet

But, I’m getting ahead of myself.

OK. Back to our quatrain. I also like the non-specificity of the word “this” in the third line for all of the same reasons that pertain to the first line. But, now the second line is weak and needs work. While it adheres to our meter and hits the accents at the right places, it has an awkwardness, a clunkiness, to it. It doesn’t flow. It sounds forced. It sounds, to my ear, like a line that shouldn’t be there. It should be better. Whether the third line stays the way it is depends on what happens to the second line. But, I like the last line pretty much as is. The only question for me is whether the first word will be “but” or “and.” And we won’t know that until we discover the middle two lines.

So, I like the word “strong” at the end of the fourth line, which means we probably want to rhyme it in the second line. What rhymes with “strong?” Well, I think there’s an obvious rhyme in this case – “song.” It kind of fits with where we started from in the first place: Harmony. And I don’t think it will be a bad rhyme or a forced rhyme when we find the right piece to the puzzle. Let’s see if we can keep the intent and reshape the words a little. How about:

We come to this place

We sing our own songs

We can’t do this alone

But together we are strong

That’s a good start. It may get tweaked a bit more as we go along and refine. I don’t know yet whether it’s a verse or a chorus – it sounds like a good first verse opening, so far – but, we’ll let the process lead us there. This is a game of give and take. Be open to the muse, let her lead you, but be in control.

This was a little peek into part of a workshop process that I’ve honed over the years. My own, private songwriting process is different, of course, but has many of the same elements. But, the point is here to listen to words – the sounds, the shapes, the rhythms – and let them be an inspiration.

Coming up in Future installments: The Listening Book, song titles, meeting a famous songwriter, and what comes first, the music or the lyrics? The answer to the last question is “yes.”

Sunday, July 29, 2007

On Songwriting: Limitations and Opportunities - Part Two

So, what do I mean by limitations? I’m not talking about your shortcomings. (And we all have those.) I’m actually talking about structure. Specifically, song structure. More specifically, verse structure – those very precise patterns that we impose upon our music. ABAB, ABCB, AABB, etc.

Let’s pause and remember two things: 1) Back in my Blog “Mechanics – Part One” I remember that when I started writing songs at the age of 13 I had no rules. That is to say, I hadn’t learned about structure. Songwriting at that time for me was fun and easy. Of course it was – there were no rules! I was creative and wild and doing anything I wanted in those songs. Sometimes it produced good results. By accident. And not often. I did have an innate sense of rhythm and rhyme so things usually worked out. And I’m not saying that I shouldn’t have done that. Everybody’s gotta start somewhere, and everybody’s gotta write crap, and everybody’s gotta have that learning curve. As far as I know, all writers, in any literary discipline, spend a lot of time writing schlock that nobody ever sees, at every stage of their career. It’s part of the process. And, of course, creativity is good. I encourage creativity and wildness and going beyond the ordinary in your writing. But, 2) also back in that blog, I said that you have to learn the rules in order to bend them, stretch them and break them.

Sometimes, one’s attitude can alter perception. You can look at a structure, know you have to work within it, and view it as something that limits you and your creativity. If you have an ABAB structure, for instance, you know that every other line has to end with a rhyme (the A lines rhyme and the B lines rhyme). And, depending on your structure and time signature, etc., you only have so many beats in which to put your rhymes and get your message across. I call it “economy of word.”

(Most Western music, especially pop music, is divided into segments of eight beats in some way. It might get counted as four or sixteen, but it always has something to do with eight. There are many people more qualified than I to teach music theory, so this is as far as I’m willing to take this thread. But try an experiment: turn on the radio to any station playing modern music – Pop, Rock, Hip Hop, Alternative, Folk, Country – and listen to any random song. Start counting. You’ll see, or hear, that everything divides neatly into eight. Note: don’t try it with Jazz, Broadway, or Post-modern. And in the Folk and Country genres you may occasionally get something in three, but that’s the exception.)

Trying to fit everything neatly into a structure can be frustrating. And it can be (should be) challenging. But “challenging” is a good thing. You should be determined to rise above challenges. They should push you in a positive way. I’ve taught myself to look at what could be viewed as constraints instead as creative challenges, as opportunities to stretch my creativity. How can I say this in the most effective and most poetic way, using only the words I need to use that will fit into this structure? Economy of word. Refer to my essay “Wasted Words.” Every word is important. You cannot afford to waste any.

I approach it as if it were a puzzle. And it actually gets very exciting. I love the feeling of finding that perfect fit. It’s a triumphant moment. But, like a puzzle, you can't force the pieces to fit. They have to fit naturally, organically. It has to feel right. I’ll create a scenario, based on fact, to illustrate:

I’m working on my song “Edge of the Ocean.” I don’t have the title yet, but I know it’s going to be based on an image that someone put into my head. A teacher, referring to teachers who come back to school in the Fall and have to start over again with students who don’t retain information over summer vacation said, “it’s as if Moses kept getting to the edge of the Red Sea, but had never been able to cross it.” Hmmm, good image.

Right around the same time, I’m reading some Torah commentary about the story of Abraham and Isaac. The author points out that at the moment when Abraham held the knife over the tied and bound Isaac, in those seconds before he became aware of the ram, the fate of human history hung in the balance. The entire future of Judaism rested within Isaac. Had Abraham not noticed the ram and plunged the knife, there would likely be no Jewish people (and thus no Moslems or Christians). Hmmm, another compelling image.

Can these two ideas work together? What can I say in this song with these images? What’s my message? The thought process begins. (See “Wasted Words, Parts One and Two.”)

I have this riff I’ve been playing around with, maybe something will fit. I start playing around with the riff and some chords. I start singing some words. “Are we standing at the edge of the ocean…?” What was that image? Trying to get across, but can’t. Frustration. “Are we standing at the edge of the ocean / just to keep our feet upon the shore?” OK. That’s strong. That’s my A and B line. Do I want to go ABAB or ABCB? Well, what rhymes with ocean? “Devotion” is a pretty cool rhyme. But can I make it work without being corny or trite? Let’s see. I’ve framed the first line as a question. Maybe I should carry that through. “Are we holding close to our devotion…” “Close?” How about “tight.” “Are we holding tight to our devotion / in our grip…” Yeah, “tight” suggest “grip” and that’s a good pairing. What rhymes with “shore?” (I go through the alphabet, I use rhyming dictionaries.) Lots of things rhyme with “shore” but nothing is jumping out at me as a strong rhyme, as a way to end my next line. Hm, too bad. “Shore” is a strong word and creates the image I want. But let’s see what happens if I change it…need a synonym…“land?” “…just to keep our feet upon the land?” What rhymes with “land?”

The process carries on until I end up with:

Are we standing at the edge of the ocean

Just to keep our feet upon the land?

Are we holding tight to our devotion

In our grip or is it slipping through our hands?

It’s a pretty strong quatrain. And the melody is also strong, so far. Now, there are a couple of other things to point out. I had the opportunity to employ some internal rhyme: “grip” and “slip.” In the line it’s not a perfect rhyme, but it’s in there. And listen to the feet, the accents, the buoyancy it creates. “In our grip or is it slipping through our hands?” Also, because “hands” is plural and “land” is not, it creates an imperfect rhyme. But it’s close enough. I’d rather sacrifice that bit of imperfection for meaning. And as a sung lyric, it’s a barely noticeable sacrifice.

So, now I’ve got an ABAB pattern. But my verse is far from complete. I need another section. I’ll spare you the internal monologue, but I break the mold a bit and come up with three lines that rhyme. So, in effect, I’ve got an A section and a B section which all together forms an ABABCCC pattern (don’t look at how it’s laid out on paper, count the beats):

Are we standing at the edge of the ocean

Just to keep our feet upon the land?

Are we holding tight to our devotion

In our grip or is it slipping through our hands?

Have we been brought to the edge

Never to have crossed?

Had we entered the desert

Never having gotten lost

Would we still fight for freedom

No matter what the cost?

Now I’ve got my patterns and structure established for the verses. I’ll stick with it through the rest of the song. I’ve imposed a limitation – ABABCCC. Now, all the verse need to follow that formula. But it’s not a limitation. It’s an (all together, now) opportunity. An opportunity to use your skill with words and wordplay, and invent the best possible lyric for the situation within the structure, economically and poetically.

Turn those negatives into positives. “You can’t do it that way” really means “OK. Then I’ll do it this way. And It’ll be even better.”

It’s a good life lesson, too.

Wednesday, July 25, 2007

On Songwriting: Limitations and Opportunities - Part One

I won’t spend a lot of time (or waste a lot of words) on definitions. It’s not my intention to make this an essay about how many different structures there are and what their names are, or what exactly is a “foot,” or why I think “meter signature” is a more accurate term than “time signature.” But ask me the next time we’re in a social situation. It’s a great conversation for sucking the life out of a party. There are plenty of text books and websites that cover the terminology and the “book learnin’.”

No, we’ve covered the basics, and built this common foundation so we can talk more about the psychology of songwriting, the emotion of songwriting, the passion of songwriting. As I’ve said before, good songwriting is not just about slapping words together. You may be able to put together a quatrain…sorry…four lines that rhyme, and even have a message in it, but is it compelling? Does it grab the listener? Is there subtext?

One of the most powerful anti-war songs I know is “Christmas in the Trenches” by John McCutcheon. I’ve heard it, and even sung it, many times, but it never fails to stir emotion in me. It’s a rare listening when I end up with dry eyes. (The song really needs to be heard, or read, in its entirety to get the full impact, but for brevity I’ll only cite part of it here.) It’s based on a true story from WWI when, on a cold Christmas Eve, a German battalion and a French battalion, engaged in battle, engineer a temporary truce, play soccer, share chocolates and photographs of loved ones and sing Christmas carols together. By morning each side goes back to its own trench to begin the “work of war” once more.

Now, an inexperienced songwriter might render the last verse like this:

We all know that war is wrong

Can’t we all just get along?

Together we can make it right

We’re all one family, why do we fight?

OK, that was just off the top of my head, and if I were a second grader, it might get high marks. But you get the idea. There is a message there. One may even be able to put a strong melody to it. But is it compelling?

Maybe I can ratchet it up a notch:

In battlefields we’ve cried and bled

In graveyards we have mourned our dead

And the prayers they’ve said for loved ones dear

Could have been said for me, right here

Better. Maybe.

But go back to what I said in “Wasted Words, Part 2” about putting your listener in the song, personalizing it for them, making it real and relatable. McCutcheon framed the song as if it was a story told by one soldier from his perspective. We experience, through his eyes and thoughts and memories very specific sounds and sights, the bitter cold, the tenuous respite from killing and the temporary camaraderie. And he does this all with a steady eye on the poetic. He stays away from cliché and triteness. His last quatrain is this:

My name is Francis Tolliver, in Liverpool I dwell

Each Christmas come since World War I, I've learned its lessons well

That the ones who call the shots won't be among the dead and lame

And on each end of the rifle we're the same

It’s simple. It’s eloquent. It’s powerful. (Especially in context.) So, make the most of your choices. This is the whole crux for me. I’m about to reveal a simple songwriting philosophy of mine that has also served me well as a life lesson: Turn what look like limitations into opportunities. One old cliché might be the one about one door closing and another one opening. Turning limitations into opportunities; Imposing structures and making the most of them. We’ll continue that thread in Part 2 of this Essay.

Wednesday, July 04, 2007

Who I Don't Like

My musical tastes are pretty diverse. It took a long time for that to happen. In Jr. High and High School, I rarely listened to what anybody else was listening to. I never got into Led Zepplin or Three Dog Night, for instance.

I did like Paul Simon, James Taylor, Peter, Paul and Mary and Doc Watson. Still do. And I’ve always liked the Beatles.

In high school I was in the Heights A Capella Choir, an award winning musical organization doing some very complicated music from many different genres. We even did Gilbert and Sullivan operettas. And I did some musical theater. So I was exposed to lots of different kinds of music. I just never got into anything that was very popular at the time. It took me until after I graduated college, around 1982, before I started to appreciate the Rolling Stones.

I didn't like to listen to much music. Mostly, I wrote songs. But my writing suffered. Not only because I was a teenager, and few teens have the maturity to write a really great song (though some do). But, because I wrote in a vacuum. I was unwilling to listen to or appreciate most pop music.

I love a lot of music now. But first…

I will disclose, here and now, naked and in public (sorry for that mental image), for all to know and pass judgment, my three least favorite singer/songwriters. Now, I realize I’m in the minority here and, in some cases, my admissions about this have been known to cause riots. But music is so subjective. Everyone has a different sensibility. As it should be. This is what makes music and art and The Arts and Culture and pop culture what it is. No one can appeal to everybody. But the trick is, depending on how one defines “success,” to appeal to as many people as possible.

And before I tell who my three least favorite singer/songwriters are, let me say this: I can defend my statements. I can present a cogent argument about forced lyrics or weak melodies or useless rhymes or sentimentality or any of the other things I don’t like about their music. But I won’t do it here. If anybody wishes to engage me in a discussion, feel free to email me. But neither of us will change the other’s mind. Because art is not about an intellectual debate. It’s about gut reactions.

So, it may surprise you to learn, if you know what kind of music I like and write, that my least favorite singer/songwriter of all time is Harry Chapin. I can hear your sharp intake of breath and feel your metaphorical daggers coming through the computer monitor. But I don’t like his songs. Never have. I appreciate Chapin as a humanitarian. I admire what he did with the World Hunger Foundation and how he used his fame and money for that cause. I know all that stuff. It’s his music I can’t stomach. I’ll sum it up in one word: trite.

Coming in at number two for most disliked singer/songwriter – call out the riot police and take shelter in your homes – is Bruce. Yes, that Bruce. The, so called, Boss. I know he’s a terrific performer. And I like his politics. I just don’t buy all this “

My number three least liked singer/songwriter is Neil Diamond. And I’ll make no apologies for this one. His stuff is just trash. Although I like some of the stuff he wrote for the Monkeys. But, “Song sung blue/Every garden grows one?” Gimme a break! Or, “Money talks/But it don’t sing and it don’t dance and it don’t walk?” It makes me gag. Don’t even get me started on “Crunchy Granola Suite.” OK. Get me started. I just picked up the lyrics on his website and must now share them with you:

I got a song been on my mind

And the tune can be sung, and the words all rhyme

Deede-ee deet deet deet deet deet deet deedle dee dee

Though it don't say much, and it won't offend

If you sang it at school, they're liable to send you home

Never knowin' what you're showin'

Think you're growin' your own tea

Good lordy

Let me hear that, get me near that

Crunchy granola suite

Drop your shrink, and stop your drinkin'

Crunchy granola's neat

Sing it out

Alright

Da da da da

Da da da da da

Dee dee dee dum

One or two digestible songs like “Solitary Man” or “Sweet Caroline” does not make up for that and the rest of his sappy, crappy inanity.

I guess I have to throw Dave Mathews into the mix. As with Springsteen, I’ve tried. Bought the CDs, listened, read lyrics, liner notes, etc. Couldn’t get into it.

Well, that’s enough of who I don’t like. For my Recommended Listening picks go to www.noahbudin.com and click on the Virtual Reality page, or just click here.

Wednesday, May 09, 2007

On Songwriting: Mechanics – Part Two

Intro

Verse

Chorus

Verse

Chorus

Bridge (or Middle Eight)

Verse

Chorus

Bridge

Verse

Chorus

Outro (or Coda, or Tag)

It varies, but that’s pretty standard. In today’s pop music the bridge may not be repeated a second time because the nature of lyrics is a bit different. And somewhere in there, there is usually (but not always) an instrumental break, but we don’t need to deal with that right now.

The verse, the chorus and the bridge are the building blocks for your foundation. Let’s understand exactly what those words mean.

According to the online source The Virginia Tech Multimedia Music Dictionary, the definition of verse is: a group of lines which constitutes a unit. Often there are several verses in a single text, and usually the rhyme scheme, rhythm, and number of poetic lines and feet are the same from verse to verse in a single text.

Lyrically, the verses are what move the story of the song along (even if it’s not a story song), they propel the idea forward.

The chorus, or refrain, is like a verse in that it is a group of lines with a rhyme scheme. But the chorus is repeated at intervals throughout the song and does not vary lyrically. It’s usually the main idea of the song, the message that gets repeated throughout. It’s where, as a songwriter, you want your “hook” to be, lyrically and musically. The chorus may or may not use the same rhyme scheme as the verses. I often try to vary the rhyme scheme to set it apart and help it stand out.

Not all songs use a bridge, but it’s a useful tool. The Virginia Tech Multimedia Music Dictionary defines it as a “Transitional passage connecting two sections of a composition.” The bridge is unlike the rest of the song musically. It may or may not adhere to a previously established rhyme scheme or pattern, or have one at all. It does more than just “connect.” The bridge gives you a chance to restate the main theme in a new way. You can change perspective or add a twist to the story. It can add a sense of heightened excitement, a sort of a tension before the climax and release. Bridges often appear before the last chorus, or sometimes before the musical break. I don’t always (or often) use a bridge, but when I do, I try to make it the “ah ha!” moment in the song – the moment where the listener realizes the deeper meaning. It adds another level or layer to the structure, or maybe it reinforces the foundation.

We’ll get into examples of bridges and verse and choruses in the next section. You can follow this link for a good article on bridges.

The intro is a musical statement that brings the listener into the song, or introduces the song. It can be as simple as one chord, or it can state part of the melody, usually the second half of the chorus (if your chorus is the standard 8 bars, then the last four bars). It can foreshadow musically what’s to come.

The outro, or coda, is the end of the song. The end of a song can be handled any number of ways. It can fade while repeating a line or two, with or without lyrics; It can fade on one chord; It can swell on one chord; It can restate part of the melody; It can be a simple “amen” progression (IV – I); It can be a “cha cha cha” pattern…It all depends on the type of song and how you want to affect the listener, how you want to lead them out of what you just taken them through.

This is my outro for this section. Examples coming up. This is my outro for this section. Examples coming up. This is my outro for this section. Examples coming up. This is my outro for this section. Examples coming up. This is my outro for this section. Examp

Monday, May 07, 2007

On Songwriting: Mechanics - Part One

OK. Let’s talk about The Basics.

I know what you’re thinking: I don’t need to go over The Basics, I already know all that stuff. You’re probably thinking that even if you have never written a song before. Everyone thinks they’ve got The Basics covered.

But, whether you’re a novice or an experienced songwriter, it never hurts to review The Basics – or what I’ll call variously the rules or the mechanics – or look at them from a different perspective. Because, it’s how you use those basics, those mechanics, that will set you apart from other songwriters. It’s how you follow – and break – the rules that show you off as either skilled or inept. Just as there is a fine line between genius and insanity, how you use The Basics in your songwriting is the line between understandable and indecipherable, nonsensical and innovative, inviting and inaccessible, “hooking” the listener or leaving them floundering.

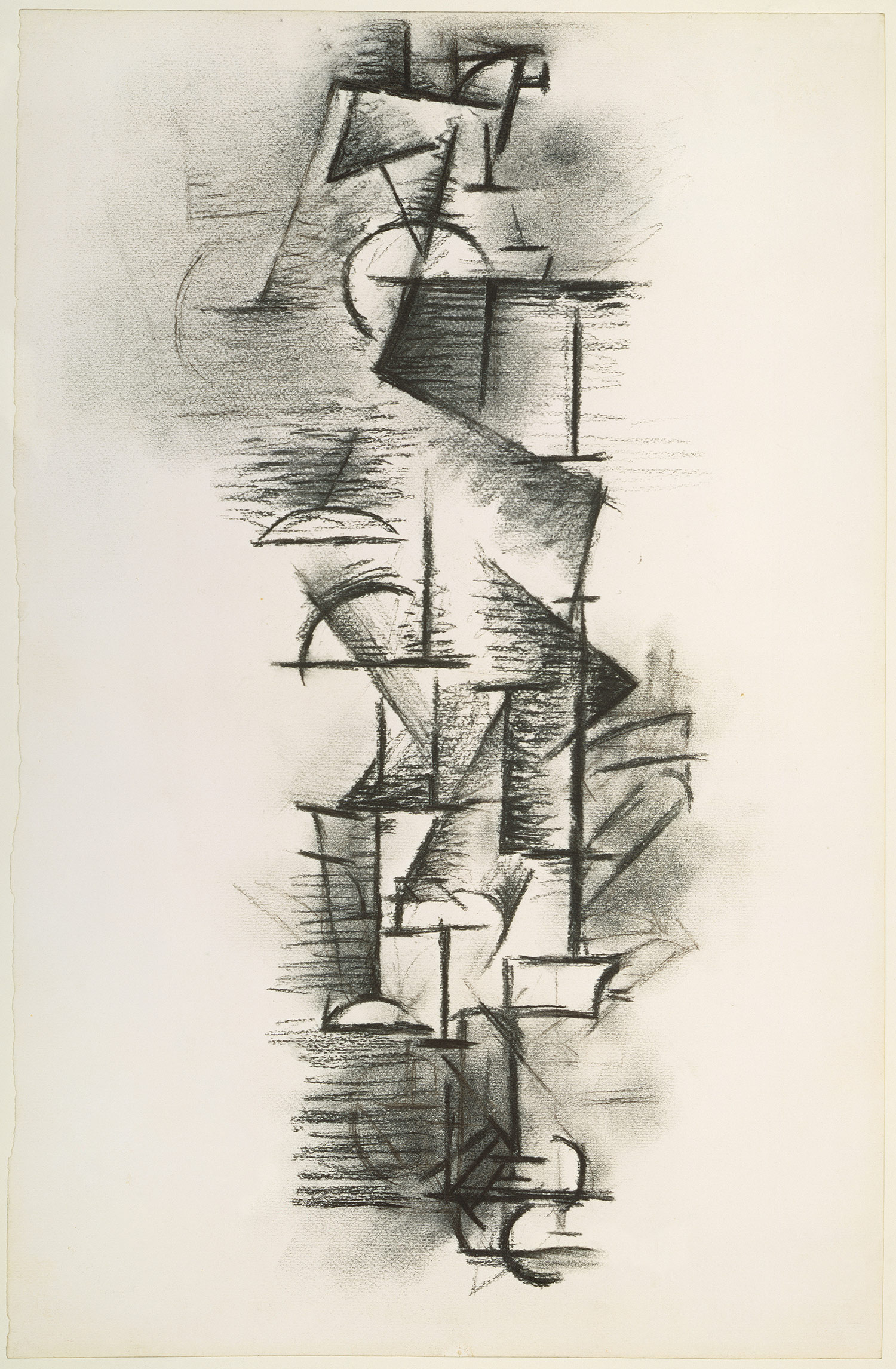

I’ll illustrate this metaphorically and anecdotally. My metaphor is Picasso. If you only have a cursory understanding and appreciation of art, and view one of his Cubist offerings, let’s say Female Standing Nude (charcoal on paper, 1910),  you may recognize it as “good,” but you may also be inclined to dismiss it as “doodling” or “something your four year old can do.” It may look easy, but try to recreate it and you would probably fail miserably. That’s because Picasso didn’t start there. He learned the rules, the mechanics, of art first. Or, take any one of his Surrealist works – seemingly unrelated objects thrown together, body parts not where they’re supposed to be, eyes misshapen and unaligned…but still, it’s intriguing, beautiful, masterful. That’s because Picasso knew The Basics, the rules, the mechanics. He spent a lifetime studying them. And he knew how to reinvent them and break them and bend and alter them. He understood Realism and could produce it. He understood shape and form, light and shadow, line and color. And with that foundation, he could expand and invent and innovate.

you may recognize it as “good,” but you may also be inclined to dismiss it as “doodling” or “something your four year old can do.” It may look easy, but try to recreate it and you would probably fail miserably. That’s because Picasso didn’t start there. He learned the rules, the mechanics, of art first. Or, take any one of his Surrealist works – seemingly unrelated objects thrown together, body parts not where they’re supposed to be, eyes misshapen and unaligned…but still, it’s intriguing, beautiful, masterful. That’s because Picasso knew The Basics, the rules, the mechanics. He spent a lifetime studying them. And he knew how to reinvent them and break them and bend and alter them. He understood Realism and could produce it. He understood shape and form, light and shadow, line and color. And with that foundation, he could expand and invent and innovate.

When I was just starting to write songs (at age 13), I had no rules. I had, of course, listened to music, and taken some piano and theory lessons, but I didn’t really know anything about writing songs. I started making up words and putting them to music. Or making up music and slapping some words down to it. And because I had no rules to bind me, to limit me, some of the stuff I came up with as a teen was pretty interesting and new and sometimes even good. But mostly it was not. Mostly, it was amateurish and adolescent. There is, of course, a learning curve, but I didn’t really begin to blossom until I was in my 30s. (I’m a late bloomer in many facets of my life). I had a gift. But I didn’t nurture it. I just wrote songs. Whatever came into my head.

When I was in my 30s I began teaching music to middle school kids in a private school. So I started brushing up on my theory, and learning things like song structure. I started putting names to the tools I was using – verse, chorus, bridge, ABAB, AABB and ABBA patterns, internal rhyme, imperfect rhyme. I learned about symphony structure – theme and variation, secondary theme, restating the theme, breaking up the theme and tossing it amongst the sections of the orchestra rhythmically and melodically, recapitulation. I started reading interviews with, and articles about, songwriters and their techniques. All of these things helped make me a better songwriter. I strengthened my foundation and broadened my musical horizons.

A note here about broadening your horizons. Do it. Become genuinely interested in as many things as possible and read as much as possible. (I don’t spend nearly as much time reading as I would like. I could blame it on, oh, any number of things, but really it’s just discipline.) Read good fiction and poetry and biographies, see theater, do theater, see good movies, learn history, stay abreast of current events, read books of trivia, go to museums, do stuff you’ve never done before. All of this will benefit your songwriting. Really. But, more about this in another essay.

In Part 2 of this essay we’re going to check under the hood and take apart the engine so we can see how things work and understand what makes the car run. (It’s a good thing I’m using an analogy here, because you really wouldn’t want me doing that to your car.) In the meantime, here’s your homework: listen to a few early Beatles songs, like Love Me Do or I Want To Hold Your Hand or anything else from that era. I’ll get back to you.

Monday, April 09, 2007

On Songwriting: Wasted Words - Part Two

Too often I hear bad or mediocre songs that could be good or great songs. (Okay, a personal note here. I have a lot of friends who are songwriters. And as artists we all share a common trait: insecurity. So, if you’re reading this and you start thinking, “he’s talking about me, he’s talking about me!” Stop it. I am not talking about you personally. I am just making observations and sharing things that I’ve learned along the way. On the other hand, if you do see yourself somewhere in here, if you recognize something about yourself as a songwriter, don’t take my words personally, but take them to heart.)

Unfortunately, with the proliferation home recording and professional-quality recording software and equipment, anyone with enough money (or friend with a studio) can make a “studio-quality” CD and release it. Some are really good, some are not. (I know we’re speaking about subjective tastes here, but…) Every song has its place. Sometimes very talented educators and musicians write songs for or with children to teach a specific concept or topic. Those songs are good in their place. Other educators should know them and use them. But, should they be on a CD with a bunch of “filler” songs because the artist didn’t have enough material? Or on an album as filler with some other really good songs for an older audience? My opinion is no. Not everything has to be released. There are other forums in which to share these songs. Work as hard as you can to make every song you release important and as good as it can be. It’s what you’ll be remembered for (or not); the songs will be here after you’re gone. Respect your audience and treat them as if they are the most important thing in the world. Because they are – it’s not about your own desire to slap something down on tape to sell.

Okay, let’s get back to the technical aspects, the behind-the-scenes, the innards, of songwriting. Here’s another question I use as a guidepost:

Now that I know what I want to say, how should I say it? What form, what structure will be my most effective tool to get my message across? What perspective shall I take?

Just as when you’re writing prose, you’ve got choices. You can use different vehicles in which to convey your ideas. Are you retelling a story from history or from the Bible? What is the point of that story that you want to get across? Are you telling a fictional story? Are you making a list (as in my songs “Metaphor” and “Reason to Believe”)? Are you explaining a situation or idea? What voice will you use? First person, third person? What rhetorical devices will you use? Analogy, Simile, Metaphor, Parallelism, Personification, Polysyndeton (the use of many conjunctions in quick succession), Alliteration, etc.?

I always look for a new way to say something. I try to create unusual word combinations (but not obscure). I’m always searching for a unique angle. Even in a simple story song. In my song “Hallelujah Land,” it’s just the combination of those words – Hallelujah Land – that are unique and unusual. They describe a place in a way in which it had never been described, and yet we know what, or where, that place is (in the context of the song). This song is a pretty straight narrative. It starts out with me, the storyteller, talking to you, the listener, in the first person:

I’ve read a lot of books and sung a lot of songs

And seen me a miracle or two

But I’ve never seen a miracle…etc.

Then I switch into third person as I tell about the miracle. The last verse brings us back to me as the storyteller to conclude and to reiterate the point.

Musically, I used a very simple(and very common) progression for the chorus so it is immediately singable. Likewise, there is not much unusual about the verses. I wanted to write a song in the style of a 1950’s or ‘60’s folk song ala Pete Seeger. It pretty much uses the I, VI, V and VI chords. But toward the end of the verse I use the III chord after the VI chord to give it a little lift. The listener doesn’t expect it, but it’s natural and not intrusive.

In my song “Joshua’s Band” I drew my inspiration from a few different places. Musically, I wanted the song to sound like a gospel song. My main message (in my mind – refer back to Part One) in the song is stated in the tag of each verse, “If you’re waiting for a miracle to set you free/You gotta take the first step…” I had just heard, for the first time, the midrash (story) of the Red Sea splitting because one man had faith and stepped into the water before it had opened up while it still looked hopeless. There are three verses. Each verse has that tag followed by the chorus. The chorus has my other main point: You gotta give the stories a voice and pass them along.

The verses are where I had fun. I wanted to take a trip through biblical history and link it to modern history. I gave myself the challenge (we’ll talk more about structure and viewing limitations as opportunities in another essay) of depicting a different, entire story in only one line of each verse. And I wanted to find a unique perspective for each story. So I tell each story from a first person perspective and find an unusual way to state the idea:

First verse:

I was in the Garden when Eve set the table (a layered meaning or double entendre)

I was covering the story of Cain and Able (“covering the story” lends a playful tone to an otherwise pretty grim story, and the modern listener can relate to the image)

I was on the Ark and I followed the flight of the dove

I was on the mountain when the ram was slaughtered

I was dancing in the river with Pharaoh’s daughter (dancing in water is a strong image)

Had my toes in the water when the water was parted from above (foreshadowing the tag)

Second verse:

I was at the Temple for the rededication (a Chanukah reference)

I stood behind the Gallows at Esther’s celebration

I was the rock that sailed from David’s hand

I tried to get a job translating at the Tower

I marched around Jericho and I felt the power

I played the drums in Joshua’s band (This was the only time I allowed my self two lines about the same story)

Third verse:

(Here is where I break from the mold a bit and bring it into modern history. The last three lines of the verse are where I tie it all together. It’s “the reveal” when we find out who “I” am.)

I was standing next to Caesar picking peaches off the trees (a reference to Caesar Chaves)

I was standing next to Abraham when Martin had a dream (Martin Luther King)

I was on the ring of keys that unlocked Nelson’s door (Nelson Mandela)

I’ve been around for the whole human story

I am Freedom, I am Justice and I’ve felt the glory

I’ve tasted the tears and the fears and I know what for